#9 Muslims in the Israeli Labour Market

The Israeli economy is significantly dependent on cheap Palestinian labour from Gaza and the West Bank

In the aftermath of the outbreak of the war between Israel and Gaza, Israel decided to send back a large number of cross-border workers from Gaza that were working in Israel. It may sound very surprising now in the light of recent events, but there was actually a fairly large labour force commuting from Gaza into Israel. These workers have now been accused of having collected intelligence to prepare the October 7th attacks, have been detained and interrogated, with allegations of torture.

The Israeli government that preceded the current one actually expanded the number of work permits granted to workers from Gaza, a decision that the Netanyahu government, despite its much more hardline position vis-a-vis Palestinians, did not dare reverse. One of the hopes of allowing more Palestinian workers into Israel, including from Gaza, was to ease the economic situation and undermine support for Hamas by allowing Gazans to earn higher wages in Israel. But besides serving a possible security objective, Palestinian workers also fulfilled an important function in the Israeli labour market: Gaza and the West Bank have been over the years a significant source of low-wage labour for Israeli companies, especially in the construction sector.

According to recent estimates, there were nearly 150’000 workers from Gaza and the West Bank working in Israel and the Jewish illegal settlements in the West Bank. If we consider that the Israeli labour force is about 6,7 million, that’s a bit more than 2%. However, Palestinians represent a much larger share of the workforce in some specific sectors, especially construction, where nearly a quarter of the workforce is constituted by Palestinians with work permits (p. 30 of the report). It is also important to highlight that besides the people from the West Bank and Gaza who are not Israeli citizens and are therefore subject to a work permit system, 18.1% of Israeli citizens in Israel are Muslim. These also generally occupy a subordinate position in the labour market.

The ITUC produced an interesting report in 2021 on the situation of Palestinian workers in Israel, highlighting the low wages and potential for exploitation induced by the work permit system controlled by Israeli authorities. As with any employer-sponsored permit system, it induces a dependency of workers on their employer, and therefore creates greater potential for exploitation. This is because permits tie workers to a specific employer if they want to be able to stay in the country:

“When workers for G. Regev Yezum 2000 (2004) Ltd., an earthwork and infrastructure development company, carrying out work in the illegal settlement of Barkan, northern West Bank, requested detailed monthly payslips, protective gear and compensation, they were forced to sign away their rights or lose their permits. Mohammed, a 23-year old who has worked for the company for two years and is paid US$59.22 a day for eight hours’ work, explains how he had little choice but to agree to unfair terms: “when we demanded our rights, the next month he [employer] gave us a payslip ... we thought this was going to be the beginning of a process where we improve our conditions, but the following month he handed us papers and told us to sign them or lose our permits... we all signed, we had no other choice.” The document workers were forced to sign states that they have received clothing, travel expenses, pay and conditions as “customary in our area” and that they have “no complaint against their employer.”

Generally, allowing Palestinians into the Israeli labour market has been a double edged sword: on the one hand, it has allowed Palestinians to earn higher wages than they would have in Gaza and the West Bank, but it has also been accused of fostering the underdevelopment of the Palestinian economy and the strengthening of a subordinate relationship between the two economies. In the words of Amal Jamal, a professor at Tel Aviv University cited in Haaretz, while it “enabled some leveling up of the standard of living in the occupied territories, it suffocated the Palestinian economy to an extent that Palestinians can’t have their own economy.” On the other hand, it also created a substantial dependence of of some economic sectors on low-wage labour from Palestine, a dependence that sits uneasily with the constant security concerns structuring Israel-Palestine relations. Israel has sought in recent years to diversify the pool of labour it draws on for low-wage work, including from Thailand, but replacing a large pool of labour from just across the border is difficult.

Muslims and Jews on the Israeli Labour Market

I used data from the most recent wave of the European Social Survey (2020) to look at the patterns of segmentation in the Israeli labour market. This data does not directly address the positions of workers specifically from the West Bank and Gaza, but it provides data on a representative sample of individuals living in Israel with data on religion, income, gender, age and a whole range of other variables. Hence the Muslims in the sample also include Muslim citizens of Israel. This data makes it possible to look at how the Israeli labour market is segmented by religion.

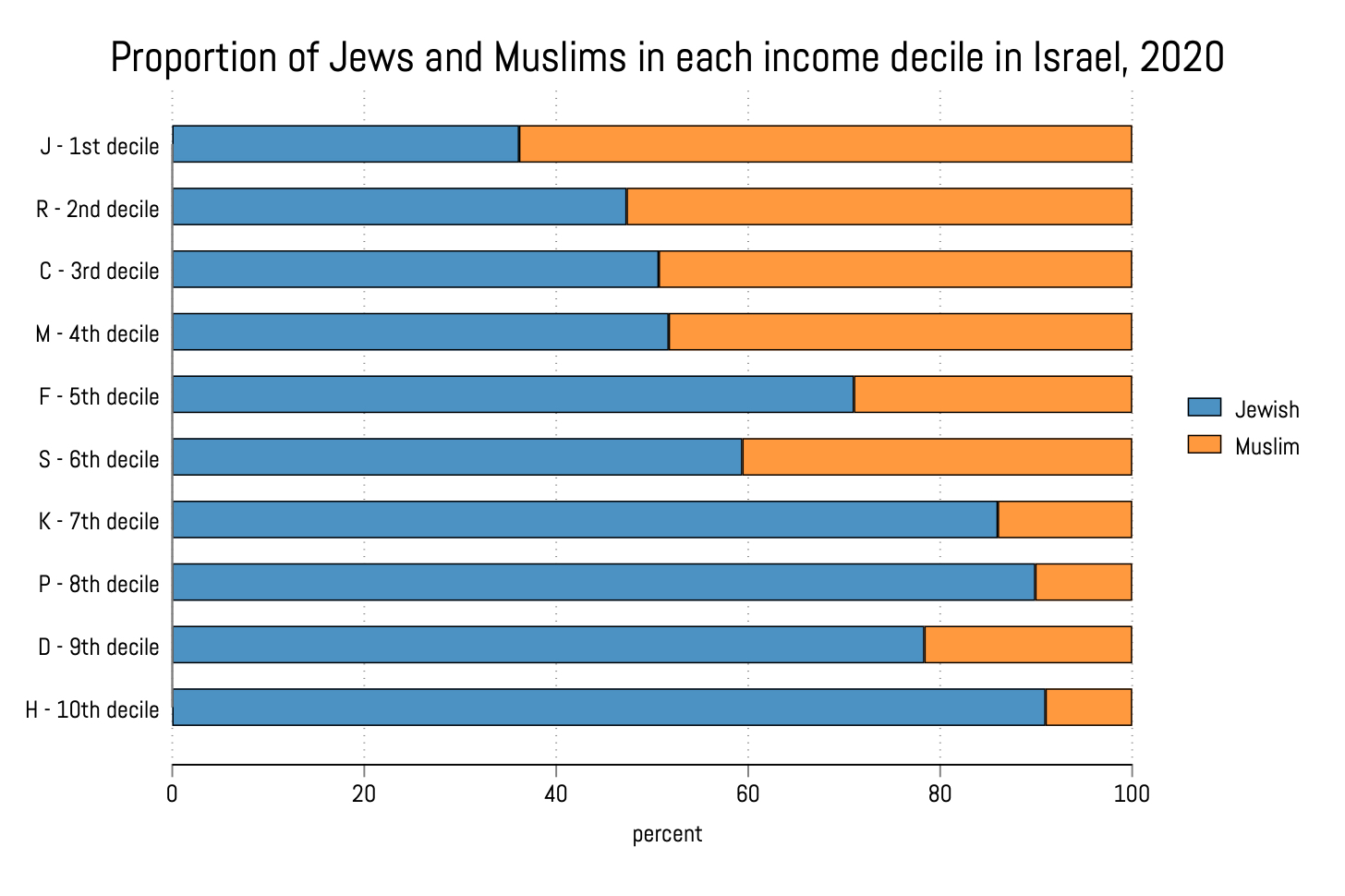

The graph below shows the percentage of Jews and Muslim in each income decile, measured by total household income. There is a clear pattern whereby Muslims are overrepresented in lower income deciles, and their share declines as you go up the income distribution. While they represent about 20% of the population, they represent about half of the workforce in the bottom 40% of incomes.

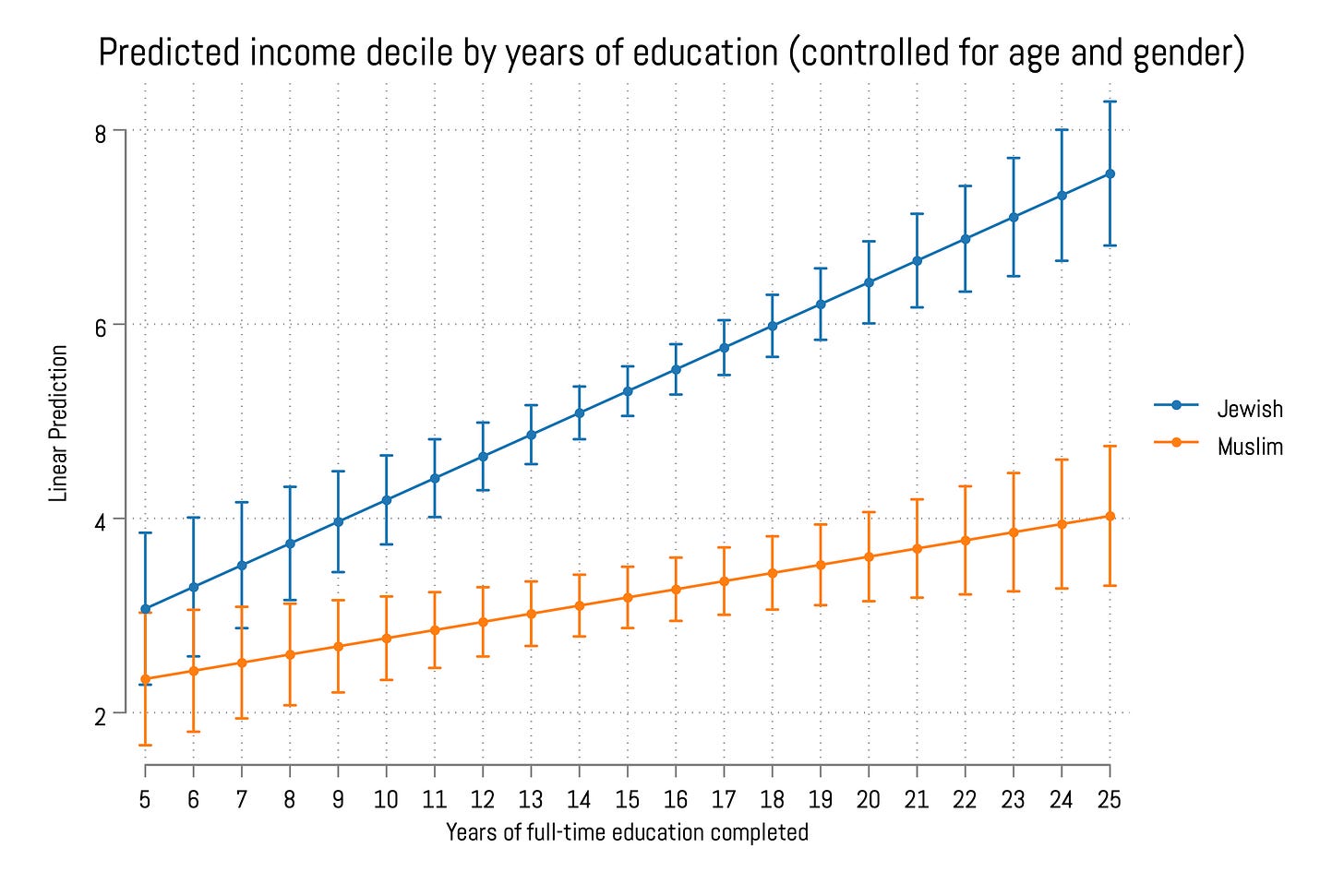

Now, in theory, it might be that Muslims are overrepresented in the lower segments of the labor market because they may have lower levels of education, which is one of the most important predictors of income. Indeed, there is some evidence that Muslims in Israel, especially older individuals, generally have a lower number of years of schooling than their Jewish counterparts. But what if we control for these factors? In the graph below, I have calculated the predicted income decile for Jews and Muslims as a function of years of education, age, and gender. Specifically, the curves illustrate the predicted income level for Jews and Muslims by education level while keeping age and gender constant. The graph shows that, as expected, income tends to increase as the education level of individuals increases, but this increase is more pronounced for Jews than for Muslims. Hence, a highly educated Israeli Jew with 18 years of education belongs to the top 40% of incomes, while an Israeli Muslim with the same level of education and the same age is most likely in the bottom 40%. This points to a clearly segmented labor market where the minority group (in this case, Muslims) doesn’t enjoy the same upward opportunities as the majority group (in this case, Jews).