#13 The State of Dutch Higher Education: From Boom to Bust

The Dutch university sector is facing a massive program of politically motivated cuts and backlash against its "anglicisation"

I have been living in the Netherlands for almost 10 years, and during this time, I have seen its higher education sector, where I am employed, transform significantly. The sector has shifted from substantial growth, driven by internationalization and openness to foreign students and researchers, to a grim period marked by spending cuts and backlash against internationalization. How did we get here?

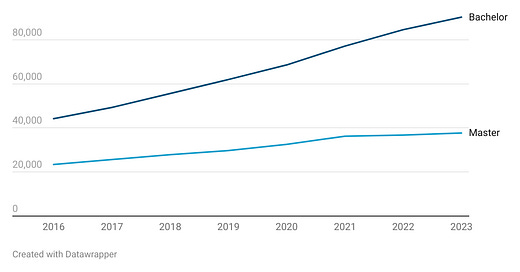

The Netherlands is a relatively small and wealthy country where most people speak good English. It is well-run (crossing the border into Belgium and noticing the bumps and potholes in the road immediately highlights the differences) and has a long-standing tradition of economic and cultural openness, dating back to the Enlightenment. In line with this tradition, the Dutch university sector has been exceptionally open to foreign talent. The ability to teach in English, especially at the master’s level, has enabled a significant international workforce to find employment in Dutch universities. Moreover, several universities have developed English-taught bachelor’s programs, attracting a significant number of international students. By 2023, 48% of academic staff in Dutch universities were of foreign origin, up from 19% twenty years earlier. Meanwhile, 25% of university students were international, and this has increased significantly in recent years, especially at the bachelor level.

Dutch higher education appealed to international staff not only because of the opportunity to teach in English but also due to the high standard of living and relative job security after completing a PhD. Unlike Germany, where early-career academics often face years of insecurity (as wissenschaftliche Mitarbeiter (research associate) or Vertretungsprofessor (interim Professor), in the Netherlands, it was possible to secure a permanent contract as an assistant professor relatively soon after earning a PhD.

This was the context in which I arrived in the Netherlands from the UK in 2015. There were personal reasons behind my move—I already had a permanent position at a good UK university—but independent of those, the Netherlands seemed like a good place to be an academic. It appeared to be in a period of growth and openness.

At that time, the Dutch higher education system was rapidly expanding and internationalizing. There were ample funding opportunities, and many universities were launching new programs and hiring staff for English-taught courses. Even in bachelor's programs taught in Dutch, there was some flexibility to include English-taught courses. Between 2015 and 2023, the number of people employed in Dutch universities increased by 40%, with the number of foreign academic staff doubling. However, student numbers grew even faster than staff numbers, and the system only managed to maintain reasonable staff-student ratios because of of the massive growth of foreign academic staff.

The expansion of Dutch higher education was driven by several factors. First, for a small country like the Netherlands, with high-quality universities and widespread English proficiency, it made sense to position higher education as an export product. In Europe, there are few options for pursuing high-quality degree programs in English outside the UK, particularly at the bachelor’s level. This gap became even more significant after Brexit, as EU students now face high overseas fees to study at British universities. The Netherlands capitalized on this opportunity, attracting many of these students.

Second, Dutch universities are funded based on student enrollment. Expanding English-taught programs allowed universities to attract international students, generating economies of scale. This additional revenue supported research and provided financial margins to promote staff.

Third, English-taught programs also helped sustain smaller departments that might not have been viable otherwise. For example, Leiden University’s BA International Studies pools multiple humanities and language programs into a large English-taught degree. It is doubtful whether such programs would be economically viable if offered solely in Dutch within the current system of higher education funding. Unlike the UK, where many foreign students come from outside Europe and pay high overseas fees, most foreign students in Dutch universities are from EU countries (Germany, Italy, and Romania are the three largest senders). These students pay the same tuition as Dutch students. Hence, expansion in the Netherlands relies on increasing student numbers rather than charging higher fees, making it harder to generate the kind of revenue that UK universities achieve from overseas students.

The backlash against internationalization has not primarily come from universities nor from students but from politics. The prevalence of English-taught programs has sparked debates about the “anglicization” of Dutch higher education. Across the political spectrum, there is widespread criticism of the extent to which English has overtaken Dutch in higher education. However, these criticisms rarely acknowledge that this anglicization was a direct response to the funding system, which ties university budgets closely to student numbers, and made anglicisation necessary. Nobody seems to want to acknowledge that the Netherlands is, well, a small country and has limited internal demand for certain disciplines. The media has reported quite extensively on a number of cases, such as Dutch literature courses being taught in English by Dutch academics with (allegedly) imperfect English. This makes for good TV, but programs like this are likely not economically viable if offered only in Dutch under the current funding model.

One key issue is that strategic decisions about which disciplines to preserve and which to scrap mostly depend on student demand. Everybody seems outraged by the disappearance of Dutch literature programs in Dutch, but these are not the programs that 18-year olds necessarily choose. For example, the decline in interest in language degrees has led many universities to cut or rationalize programs in French, Italian, or German.

The political backlash has intensified under the current government, which includes the VVD (focused on cutting taxes and public spending) and the PVV and BBB (advocating significant cuts to “left-wing hobbies” like niche degree programs). The new Minister is set to implement a massive program of cuts against which there is massive mobilisation across the sector. While the previous government acknowledged that the university sector was struggling with declining staff-student ratios and structural unpaid overwork, the current coalition plans to cut public funding further. At the same time, it aims to restrict universities’ ability to offer English-taught programs to attract international students.

This leaves universities in a precarious position. They cannot generate revenue by increasing international student numbers, remain dependent on student numbers for funding, and face significant cuts in direct public funding. This combination suggests a substantial downsizing of the university sector, which aligns with the ambitions of Wilder’s PVV, which sees universities as bastions of woke nonsense anyway. The justifications are economic, but the goals are clearly political.